Dr John FW Ndikum talks about treating patients with COVID-19 in a hospital setting, and his own experiences with COVID-19.

Hello, I’m Dr John Ndikum and today I’ll be speaking about COVID-19. So I’m going to introduce myself first of all, and I’ll go into what we found in the hospital setting in patients who we treat who have COVID-19, and then I’ll elaborate by expanding on my own experience with COVID-19.

So I graduated from Barts in London in 2010 and worked in general and internal medicine for around seven years, before going to Yale in 2017 and graduating in 2018 with a Master’s in Public Health. I then worked in the pharmaceutical industry as a sub-investigator and then as a principal investigator in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease.

This lockdown was declared in mid-March by our Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and we were also summoned as healthcare professionals to help out in the National Health Service. As you’ve probably seen and heard many of us did come down to help, but I don’t think any of us were quite prepared for what we were going to see, particularly in the hardest hit areas.

I began working in hospitals in one of the hardest part areas of the country, and what were formerly specialist wards were transformed into COVID wards and I’ve worked in one of these wards. I was shocked primarily by how quickly patients with COVID-19 deteriorated, or how they deteriorate in the present tense because it’s still going, and a lot of people are still being affected by it.

I was also very surprised that the lack of consistency in terms of presentation and differences amongst people presenting with COVID-19. So we had to work with a strategy that would catch as many people as possible and obviously prevent the rapid deterioration.

What we found is that there is no typical presentation of COVID-19. If there were to be a typical presentation would be using that word very loosely, and you’d have patients come in usually with shortness of breath, a cough and a fever. Some people just come with one of those symptoms or sub several of them, and others would come with the more unusual symptoms such as loss of smell and the loss of taste as well, loss of those senses and muscle like myalgia so a little bit more typical of flu.

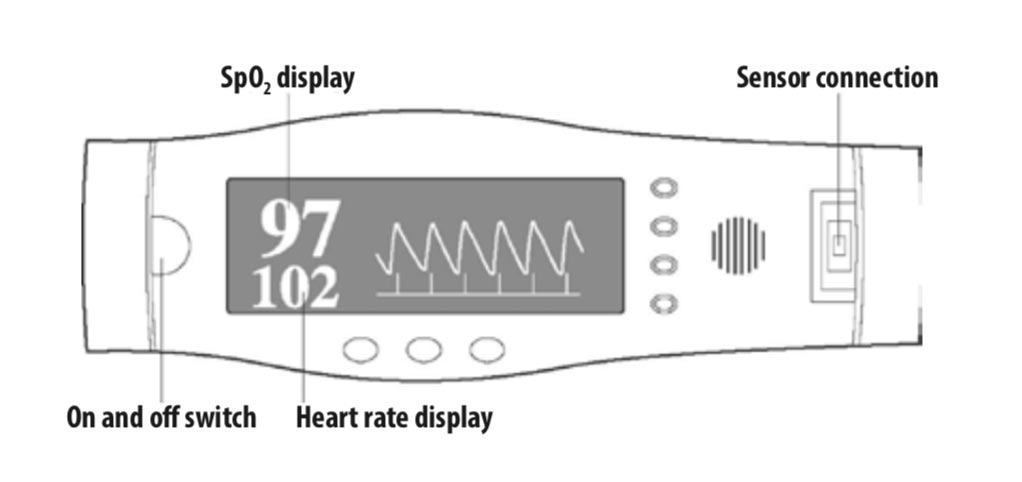

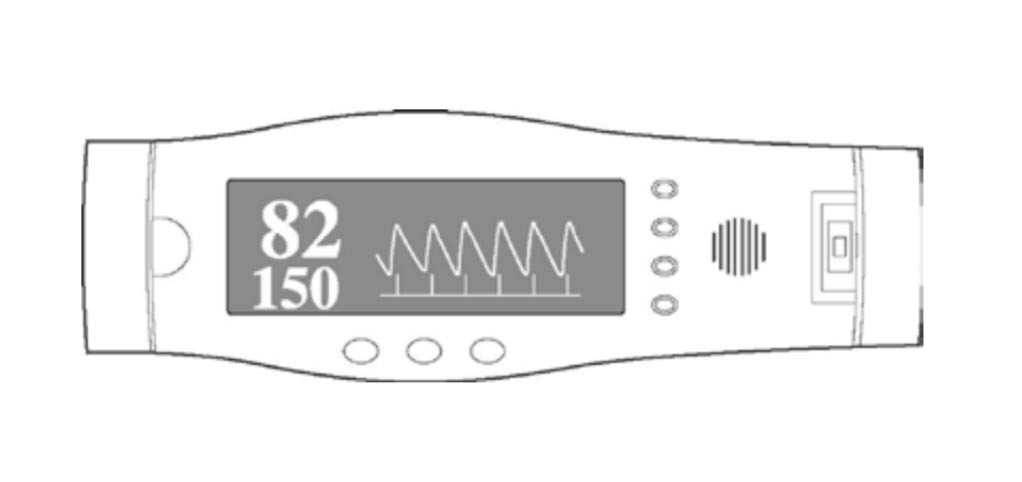

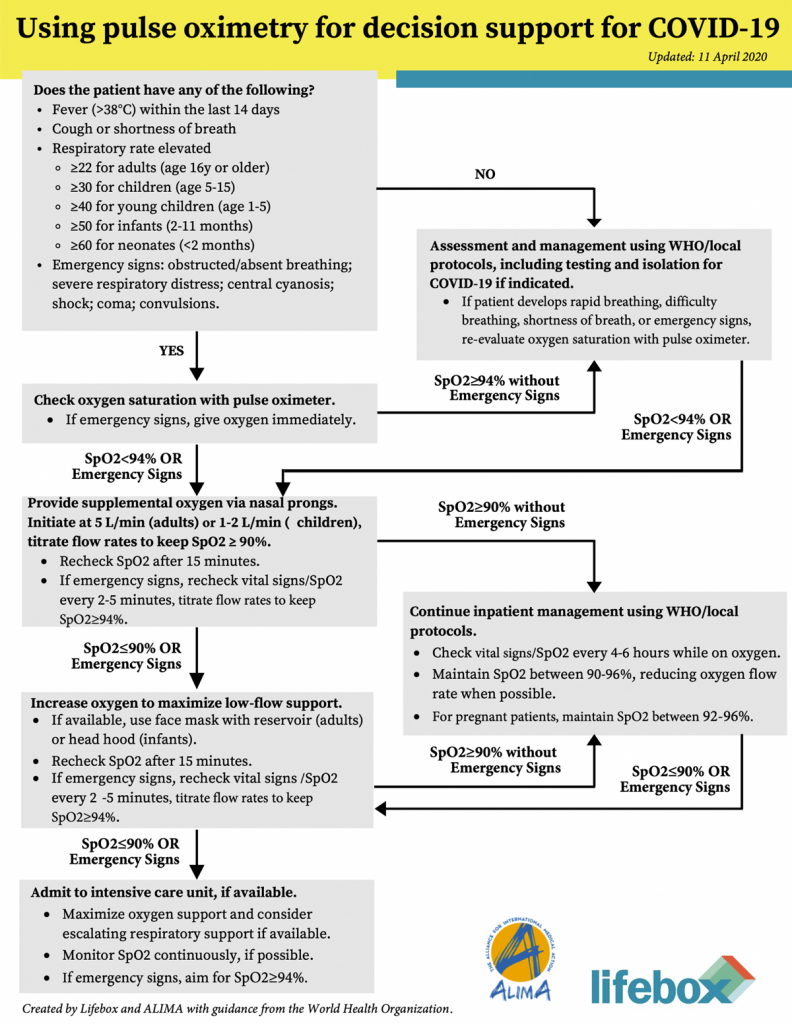

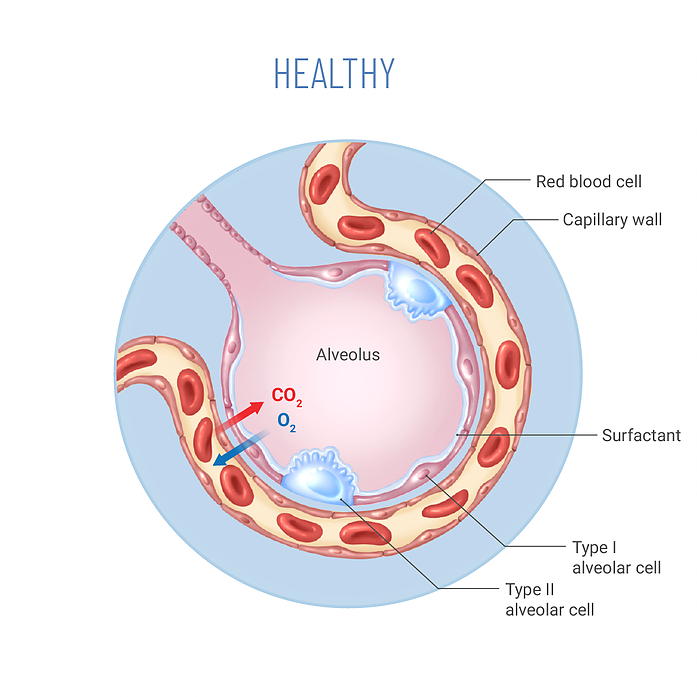

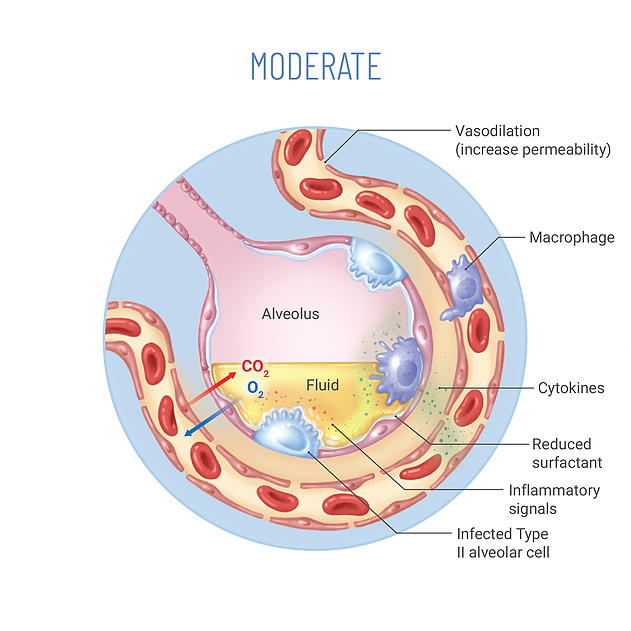

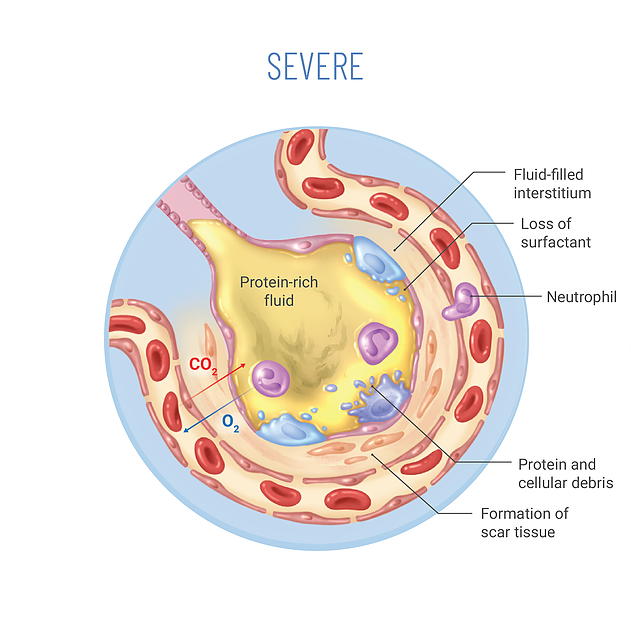

But what is shocking in this is how quickly people deteriorate, and more surprising is that you could have people that recently called in the news ‘happy hypoxics’ where they’re generally quite well, they look well, but when you do a saturation probe to look at the level of oxygen they are very hypoxic. So when someone’s oxygenated someone without underlying lung condition you’d be aiming for oxygen saturation above 94 percent, usually ideally above 97 percent in patients who have got a hypoxia oxygen level of around 80 percent sometimes even less but they appear well.

So what we’ve had to do is work very closely with the ITU teams, find patients who all those are high-risk patients; older, high blood pressure, diabetes and really we can have used prognostic markers to ascertain how quickly they can deteriorate.

We find out that there is a correlation between certain markers namely LDH, d-dimer and ferritin, and while those might be generally raised in infection they are significantly raised in patients with COVID-19. We also find that lymphocytes are low, and magnesium phosphate are also low, and those are usually telltale signs that we are dealing COVID-19. Whilst there are florid signs of chest x-raying signs of interstitial lung disease on CT scan these aren’t always there. You have COVID-19 patients who have no chest x-ray signs.

As for swabs, we know that they have a 25 percent false-negative rate, so we use them cautiously, and we use them more as an academic tool when data sets begin to emerge. For example I had a patient who had florid signs on chest x-rays, CT of COVID-19 three of the swabs were negative, but we treated them as if they didn’t have it, and we’ve seen that a lot.

A friend of mine who’s an infectious disease specialist said that it’s quite strange the virus appears to travel down, reside in different parts of our airway during different stages of the disease. So there have been cases where swabs are negative, but broncial washings are actually positive.

So it is a disease that is proving to be a significant riddle, and one thing that appears to help is using oxygen saturations as one of the primary biomarkers. What I find is that the results that these biomarkers actually act as indicators several hours before the rapid deterioration.

So I advise my friends and family members to get an oxygen saturation probe in their home, and once this begins to drop below 94 percent without a lung condition, and below 88 in people with a lung condition, then you can have the evidence there to seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

That’s my own personal experience. I did reflect on it in hindsight once I lost my sense of taste and sense of smell. I began to have very mild symptoms about a week, after two weeks before the loss of sense of taste and also the sense of smell. It was initially just a tickly throat that then evolved into a dry cough, that then became productive.

I also had a blocked nose and sneezing, but I think that’s associated with my hay fever, so it’s very easy for me to dismiss that and to think that it wasn’t COVID-19. What then developed was myalgia, so I had this muscle ache, and then this extreme lethargy and fatigue which I put down to just working very hard in the hospital, and obviously doing a little bit of workouts at home.

But I did began to get quite worried was when I began to have fever and night sweats at home. I’d wake up drenched in sweats or rather my wife would know when I was soaking in sweats. That happened for a couple of nights, and again I put it down to just the chest infection, just bad hay fever, because there was no real indication, my saturations were 97 percent throughout, and so there was no real reason for me to suspect that I had COVID-19.

Because when I lost my sense of taste and my sense of smell that I physically became better. If these are still gone, these senses have gone, that for me that was obviously the clincher.

So what we’re seeing here is that there’s no typical presentation of COVID-19. The best thing that we as physicians and obviously those in the community can do, is try and utilise reliable biomarkers to catch the disease before things begin to deteriorate.

My experience, my anecdotal experience, I can’t say this is evidence-based, has been to use saturation probe in the hospital setting. LDH, d-dimer variative which act as very early part biomarkers to act as indicators to bring in ITU support, or at least have ITU be aware, and keep the patient on their radar. What’s important is that data, get more and more data is forthcoming from different countries in an honest fashion, so that we can build robust data sets, see the correlation, see the pattern and see what needs to be done to reduce mortality and morbidity from this disease.

Thank you for your time have a good evening and stay safe.