A conversation between two long-term care physicians about how COVID-19 has changed the way they provide patient care.

Anne: You told me last time that there’s really not that much difference in terms of pre-COVID in planning when you’re dealing with residents and their families, because a lot of the preparation pre-COVID days you’ve already done. Right when they come in when they’re admitted. So the first question is ‘how have things changed due to the current pandemic?

Brian: I think that the biggest thing that I’m appreciating from the nursing staff as we’re talking today, I’ve even met this patient yet in the flesh I just went over orders and stuff along that line, and I see from her chart that somebody whether it was the nurse practitioner or the nurses got a no see a DNR order on the patient right from the get-go when she came in. And I would bet that there’s a little bit more importance put to that during COVID-19 because the fact that god forbid if we do get it into the institution it’s gonna be very very hard to keep it from going from floor to floor to floor.

It was actually back in early 2000s that I forget what the outbreak was that we had in seniors health center, and at that point in time couple of the floors got together on one floor for meals and through some donations and the North York Foundation whatever they were able to reconfigure some of the space so that each of the four floors has a dining area on their own floor. So that there’s a at least an opportunity to try and isolate any kind of outbreak onto one floor, and we’ve been successful to do that many times over the years that I’ve been there. So that was a huge plus. Nursing homes of the future I have no idea how they’ll do it now we’ll probably all be single rooms, how they’re gonna do it to existing places I can’t imagine, I just can’t imagine.

Anne: What’s the most number of residents per room that you have?

Brian: We have some ward rooms, four bedrooms not a lot of them, but certainly at least a couple of floors so that, oh well, four floors only single rooms. But I guess on the others we probably have at least six four bedrooms in the in the institution, at least that, and almost all the other rooms are double, and the fourth floor is sort of the executive floor. It’s more costly because they’re almost all single rooms, and some of them are even like husband and wife not a lot of those, but sometimes there are a husband and wife in some of the larger rooms.

Anne: So has Infection Control commented whether we should be using fewer of the I guess they call ‘Ward type rooms’ and more of the single rooms, if you have a capacity?

Brian: It’s come out in directives but I don’t know specifically who from, where, but that’s gotta be something that they’re going to have to look at, but as I said what they can do to existing structure … I mean I don’t know, you’re talking about major and even then you couldn’t you could theoretically convert them into two two bedrooms, but it would still take a fair bit of construction. You know the suction and oxygen the whole business, but otherwise you’re decimating the number of residents you can have in the institution. Craziness, but moving forward I would bet that that’s what they’re gonna have to do.

Anne: If you are building a new long-term care facility?

Brian: I would put in all solitary rooms, all single rooms.

Anne: What about the rooms where they share a bathroom in the middle? They look like single rooms but they’re actually doubles, but they have a bathroom in the middle, is that safe during pandemics?

Brian: No I mean no but even our double rooms it’s one bathroom in that suite, there’s not even like one on either side both of them using that bathroom. The four bedroom it’s one bathroom so as I say the retrofit I can’t I can’t imagine but new construction I would bet that that will be where it’s all at.

Anne: Solitary rooms with a bathroom in each room.

And the other thing is you have enough rooms maybe not every room but you have for the sake of argument a quarter of the rooms that have the negative pressure ability, to really, really isolate the patient. A respiratory or that kind of problem. I mean the two major two major problems that we get must be the same as you is either a GI outbreak you know like Norwalk, and we’ve been very very fortunate in my 20 years maybe two or three outbreaks maybe like not a lot. But then we’ll get influenza outbreaks.

So then the real question is can we confine it to just one floor or two floors, of the four floors, so they really try and wiggle around the staff to not do a lot of moving from floor to floor or anything along that line. Will they there’s one staff cafeteria type room? Is that a good idea do they have to take much more shift lunch times, spread it out more. New world, I don’t know what all the answers are to this but it’s got to be a bit of a new world because even then, if you’ve got the floors isolated if the staff can then congregate, somebody from the first floor, the third floor the fourth floor going to meet for lunch in the cafeteria, sit at the same table. I don’t know.

Anne: I think we need bigger tables in our in our place because in our nursing home the tables are not six feet, you’re not sitting six feet apart and now that we have this directive of six feet. I’ve never had experience with this before, this is the first time COVID has made it the first time we actually have to sit six feet away, we’ve had lots of gastroenteritis before but they’ve never had to sit six feet away. So I think going forward I think we would probably have to make bigger tables, or longer tables. The hallways need to be a little bit wider, and I think we would have some units where there are doors. I noticed in yours you have doors that separate the wings, but we don’t have any doors, people only one wing to the next. We’ve got a nursing station in the middle and it’s wide open from one side to the other.

Brian: This was a fire fire code type stuff, they’re all fire walls because we every now and again do have a fire drill, and those doors just close automatically, and all hell breaks loose when they do the drills. Fortunately they usually forewarn us, but yeah.

Anne: We have a lot of wanderers on our floor too, and I noticed that at your home with the doors they’re being shut, it helps to keep the people that wander if they’re COVID positive, you just keep them behind the doors, whereas in ours they kind of move all over the place and we have to have bodies to actually get them redirected back to the rooms.

Brian: Oh yeah yeah.

Anne: So you mentioned before that talking to their families is so important when they are admitted, can you remind me again what did you say about when they come in and then you have the initial conference which is usually between one to six weeks I guess, after they come in, you talk to them about these goals of care. How do you put it to them?

Brian: The goal is to try and see them, speak to them in person within a couple of weeks and I review all of my medical information with them and you know what conditions I’m aware of, have I missed the boat on anything? And I once again especially if dementia is part of the diagnosis I try and advise them right up front that you know this is not going to get better, maybe it’ll stabilize somewhat but it’s gonna gradually get worse and worse and worse, and unless something else takes your loved one the dementia itself will be the terminal event. And how long have you had it average length is about six to seven years from initial diagnosis to the end, so you got to be prepared that you know one day your mother is gonna forget how to swallow, forget how to chew, and not be able to eat. So we’ve got to prepare ourselves emotionally and mentally that that might be.

And then the the big talk. It’s been an adjustment over the 20 years as far as what are what we get them to sign so to speak. At one point in time when I first started there there were like four choices as to what to do as far as end-of-life or advanced care directives. Right now it’s basically CPR, no CPR. And ideally sometimes we’ll talk about transfer to hospital type situation, and I explained to them that if something acute happens that is reversible, something like falling and fracturing a hip, or a fracturing a wrist, it’s unfortunate if that were to happen, hopefully it won’t happen but of course we would send your loved one to the hospital to get x-rayed and tested.

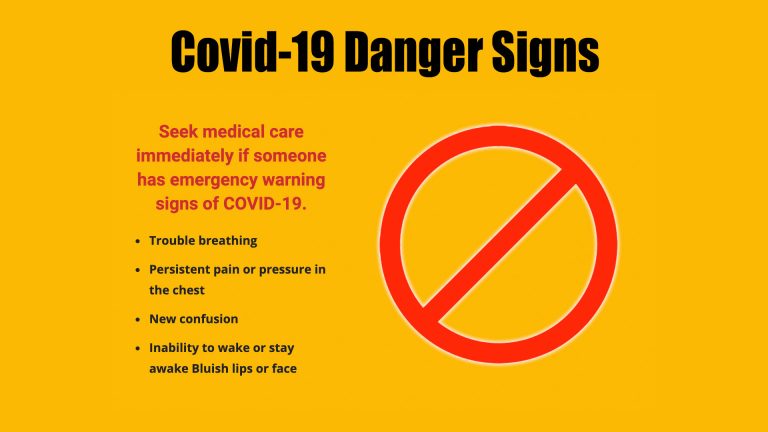

But otherwise if it’s just a significant event, but one that is not likely going to be easily reversed: a bad pneumonia, a heart attack, a stroke – do you really insist that we send the patient to hospital? It’s just not by any means that they’re going to get better or do you allow us to keep your loved one as comfortable as we possibly can here, we’re very comfortable with the fact that people do pass away here .. it’s it’s reality and that somebody’s got to die sometime. We’re not in a hurry to have that happen, but it will happen sometime, and just going to a hospital it doesn’t mean you’re gonna recover, and if anything that I put it on myself; from a personal standpoint I can’t imagine anything more disruptive that when you’re in your last hours or days that you’re taken by ambulance guys who you’ve never met before on a stretcher outdoors, it might be middle of winter, into an ambulance to go to a hospital. A bunch of people again who don’t know you, rather than staff who have been taking care of you for six months, six years. And it doesn’t mean doesn’t mean you’re gonna get better. So I couch it in those kinds of terms …